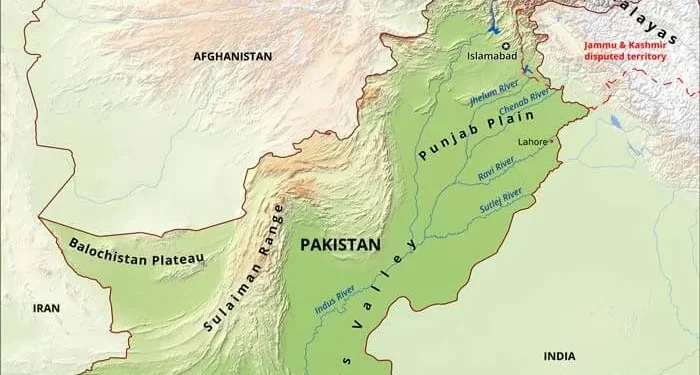

The above map of Pakistan is not correct in its depiction of Jammu and Kashmir, which rightfully and legally belongs to India. Pakistan is in illegal possession of what it calls ‘AZAD KASHMIR’, which in reality is illegally occupied Kashmir by Pakistan.

Sir Halford Mackinder warned that “land power defines destiny.” Pakistan governs territory without commanding comfort. It occupies land that refuses reassurance.

Lack of Depth

I have spent a lifetime studying Pakistan without ever living inside it. My career placed me not in its markets or parlours, but along its periphery, on icy ridgelines, in forward posts, and across the unforgiving grammar of military maps. Over the years, Pakistan ceased to register in my mind as merely a state or even an adversary. It resolved into something older, more elemental, a disturbed landscape wearing the costume of a nation. Nations, I learned early, do not select their insecurities. Their terrains assign them. In Pakistan’s case, every ridge, every river, every open plain delivers the same strategic verdict to its rulers: vulnerability.

Pakistan’s philosophy of war is not one of endurance but of disruption, built less on strategy than on spectacle, less on strength than on deception. Its history, its crises, and its fears enter from the east, across flat lands that do not forgive delay. To Pakistan’s eastern edge lie the Punjab plains, fertile, congested, and lethally exposed. There is no mountain chain to absorb force, no dense jungle to slow movement, no river that cannot be crossed. The frontier lies naked on the earth, like an incision that never closed. Lahore and Amritsar are separated not by terrain but by time, minutes of flight, hours of armour. When a state is denied depth, it substitutes anxiety for distance. In such a country, defence becomes reflex, not resilience. Pakistan’s doctrine did not mature into patience. It hardened into an interruption.

“But Pakistan’s enemy does not come from its mountains”.

A glance at Pakistan’s physical map reveals its paradoxes. A mountainous crown guards the north and northwest. A generous river system threads the heartland. A vast plateau spreads across the west. A desert thins the southeast. And a precarious coastline pinches the south. At first sight, the country looks well-provided for. But geography is not what one possesses; it is what one can convert into security. Pakistan is not short of terrain. It is poor in alignment.

In the north, the Hindu Kush, Karakoram and Himalayas rise like a citadel. These mountains could shield a civilisation, if danger came from that direction. It does not. Pakistan’s threat axis does not descend from glaciers; it advances across open fields. The mountains stand where no invasion marches and fade precisely where protection would matter most. South of this stone crown lies Jammu and Kashmir, over which Pakistan draped a false narrative of grievance and entitlement. The terrain here does not defend; it fragments. Valleys invite infiltration as readily as peaks deny armoured movement. These highlands are not shields; they are corridors of shadow warfare. Terrain here generates friction, ambiguity, and perpetual uncertainty. Pakistan’s northern geography is not a fortress. It is an incubator for instability.

Rivers of Woes?

Now trace the Indus River system from the mountains to the sea. This is not merely an agricultural network; it is Pakistan’s bloodstream. The nation’s population, industry, and food security are precariously stacked along this narrow hydrological spine. Where robust states distribute critical infrastructure across space, Pakistan compresses it into water-fed arteries. The strategic consequence is unforgiving: a state with a single circulatory system cannot afford disruption. Water, therefore, is not policy. It is survival. Dams are not development. They are defence assets. In Pakistan’s strategic imagination, a threatened river is an act of war in slow motion.

To the east of the Indus lies Pakistan’s most lethal exposure, the Punjab plains. The map here offers no depth, no interruption, no asylum. It is terrain built for speed and punishment. This is the ground on which wars are decided in hours. Pakistan’s major cities sit astride this vulnerable corridor without natural shielding. When the geography refuses to cushion the impact, war planning turns nervous. And nervous geography does not breed strategic elegance. It breeds pre-emption.

Allround Defence Hollow

Westward, the map darkens into resistance. Balochistan is not merely underdeveloped; it is geologically defiant. Brown deepens into ash as terrain dissolves into distance and isolation. Roads do not unify here; they stretch and vanish. Towns sit like forgotten outposts on a hostile planet. Authority is fragile, loyalty local, and governance episodic. This land does not bend to bureaucracy. It repels it. Pakistan did not conquer this geography. It inherited its difficulty.

Further north, the Afghan frontier is not a border but a fissure. The mountains here do not divide; they protect autonomy. The Durand Line has never behaved like a boundary because the ground refuses to recognise it. Force cannot tame this frontier. So Pakistan substituted control for influence, institutions for intermediaries, and law for networks. Afghanistan, over time, became less a neighbour and more a conceptual rear area imagined strategic depth for a nation denied it by geography at home. But buffers rot. They do not defend forever. This was not a policy miscalculation. It was geographic inevitability.

To the southeast, the desert offers delay but not defence. Sand does not stop armour; it only lengthens the approach. And to the south, Pakistan narrows into the sea. Its coastline is short, exposed, and dominated by a single economic throat, Karachi. Port, refinery, marketplace, energy hub, all compressed into one vulnerable city. This is not strategic depth. It is an exposed artery. A blockade here does not inconvenience. It strangles. Thus, Pakistan watches the sea not with ambition but anxiety.

Taken together, the map teaches a brutal lesson. Pakistan’s mountains confront stability, not threat. Its plains confront threat, not shelter. Its rivers generate dependency. Its western front erodes control. It’s desert delays but does not protect. Its ocean exposes its heart. When geography denies sanctuary, doctrine manufactures deterrence. Pakistan’s nuclear posture was not born of bravado but of the map. It is not an expression of power. It is a confession of constraint.

Kenneth Waltz once observed that states develop nuclear weapons not because they seek destruction, but because they fear defeat. Pakistan’s arsenal reflects precisely that psychology. These weapons are not ornamental. They are architectural, walls built in the mind where none exist on the ground.

States confident of survival build militaries as instruments of continuity. States convinced of fracture assemble them as escape hatches. Pakistan belongs to the latter. Its forward posture, ease with escalation, reliance on surrogates, and fixation with deterrence are not choices. They are symptoms. Policies can be debated. Geography cannot. The map does not speak, but it testifies. And Pakistan testifies without mercy.

Over decades, I have watched this same map outlive presidents, prime ministers, field marshals, generals, doctrines, and governments. It outlasted slogans, alliances, and ideologies. It prescribed limits long before men debated intent. Pakistan is not haunted by religion or politics alone. It is haunted by its outline. Its territory does not reassure it. It compresses it. That, more than any doctrine, explains why Pakistan never truly rests.

Footnotes

1. Robert D. Kaplan, *The Revenge of Geography: What the Map Tells Us About Coming Conflicts and the Battle Against Fate* (New York: Random House, 2012).

2. Halford J. Mackinder, “The Geographical Pivot of History,” *The Geographical Journal*, Vol. 23, No. 4 (April 1904).

3. Kenneth N. Waltz, *The Spread of Nuclear Weapons: More May Be Better*, Adelphi Paper No. 171 (London: IISS, 1981).

(This article first appeared on the author’s blog, the General’s Warroom.)