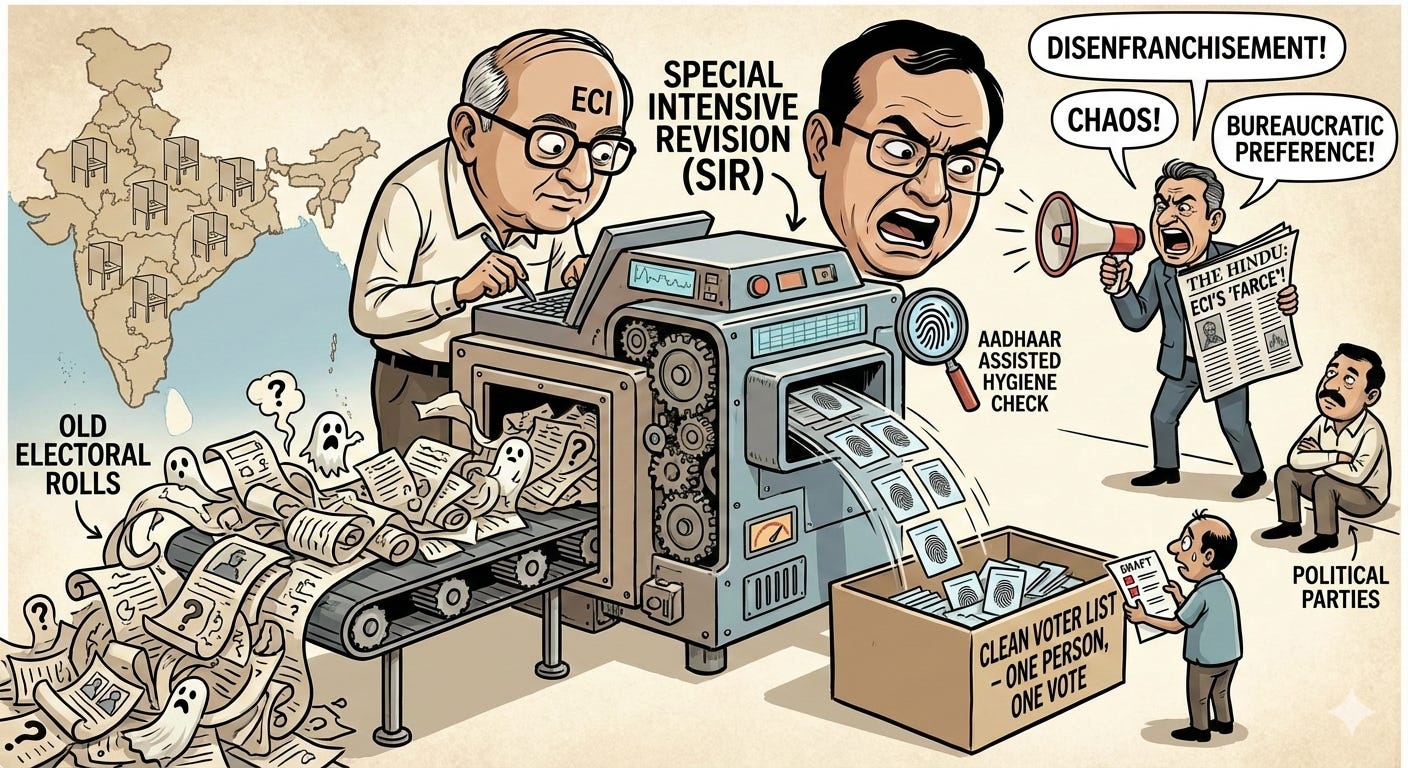

SIR has caused considerable debate in India. There is widespread criticism in the domestic media, and at times in the international media, of its methodology and the haste to conduct SIR before the impending elections in the states.

In the following essay, KBS Sidhu, a former IAS officer closely associated with electoral procedures, defends the SIR exercise by questioning media reporting.

The Hindu got it wrong:

Defending the ECI’s legal mandate and objective does not mean granting it a certificate of perfection. A citizen can insist on due process, humane verification, and robust safeguards—and still reject the insinuation that every disruptive administrative exercise is a covert assault on the franchise, or (worse) on citizenship itself. That balance—firm accountability without cynical delegitimisation—is precisely what The Hindu, of all papers, should have modelled.

Start with the law: who may be on the roll

This is the starting point that the editorial underplays. The SIR is, at core, an effort to restore the first principle of democratic equality: one person, one vote, in one place—at a nationwide scale.

Why revision is disruptive: scale, churn and imperfect records

Discomfort during a revision is not evidence of malice. It is a predictable by-product of cleaning a system in a country of this size, and cannot be casually labelled “mass disenfranchisement”. The real question is not whether a large revision is messy (it will be), but whether it is legally grounded, transparent, correctable, and executed with safeguards.

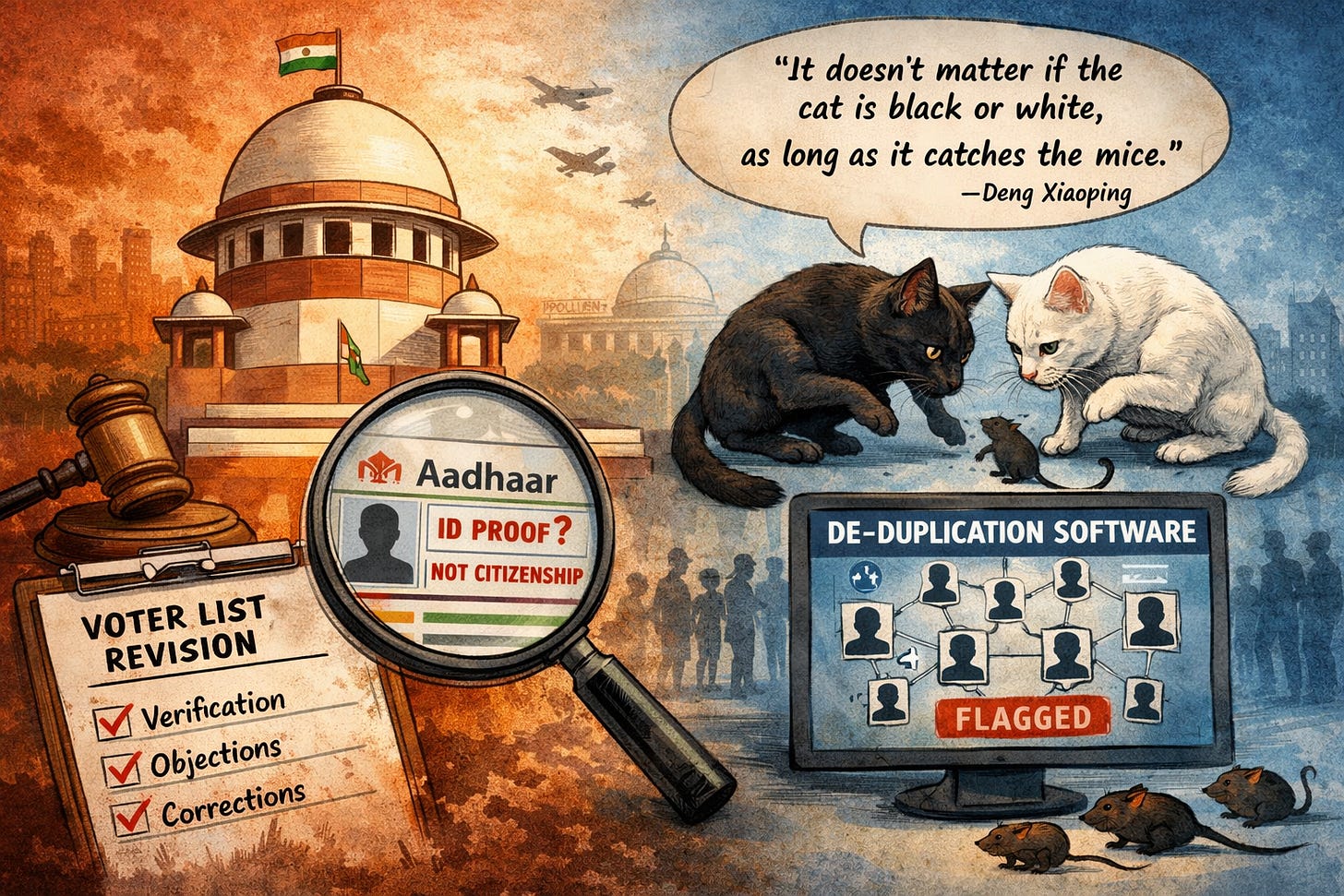

Aadhaar: not a citizenship proof—yet useful for hygiene

The relevant point is narrower and more practical: Aadhaar-linked indicators can help identify probable duplicates—the same person appearing multiple times under variations in name, age, or address, sometimes across constituencies and even across States. In an electorate of this magnitude, the inability to detect duplication nationally is not a minor administrative flaw; it is a direct threat to the one-person-one-vote principle. Sensible scrutiny, therefore, is not whether Aadhaar “proves citizenship” (it does not), but whether Aadhaar-assisted matching is used as a lead-generator followed by notice, verification, and correction mechanisms.

What the Supreme Court did—and did not do

This is where The Hindu’s rhetoric becomes particularly unhelpful. When the SIR was taken to the Supreme Court (notably in Bihar) and heard at length, the Court did not strike down the exercise. Nor did it stay the publication of draft rolls; it made clear that the process could proceed, with outcomes subject to the Apex Court’s final verdict.

Equally important, the Supreme Court advocated a more voter-friendly approach to documentation—observing that Aadhaar and EPIC/Voter ID should be accepted as documents for the purpose, while simultaneously recognising the legal position that Aadhaar cannot be treated as conclusive proof of citizenship. The ECI, for its part, indicated willingness to accommodate such practical suggestions, without abandoning the statutory discipline of eligibility.

This is the sober constitutional point that must anchor commentary: demanding improvements and safeguards is legitimate; branding the entire process “farce” when the apex court has allowed it to proceed with refinements is not.

Why deduplication software matters: the cat-and-mouse principle

In a national electorate of this magnitude, deduplication software is not a sinister shortcut; it is a practical filter to identify probable duplicates that manual methods will simply miss—particularly where the same person appears under minor variations of name, age, or address, sometimes across constituencies and even across States. Here, the correct principle is the one Deng Xiaoping popularised: it doesn’t matter whether the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice. In electoral terms, it matters less which tool helps detect duplication, and far more that the tool actually detects it—provided the statutory safeguards follow.

A deduplication engine should generate leads, not verdicts; it should trigger notice, verification, and an opportunity to contest—not automatic, irreversible deletion. That is the correct line of critique: tighten safeguards and transparency around flags, rather than denouncing the very idea of technological deduplication.

Insisting on due process is essential; declaring the process illegitimate by default is not analysis.

Draft roll is not the final roll: why “deletions” happen

Crucially, proposed deletions often reflect prima facie ineligibilities that any lawful roll must address: entries linked to deceased electors; persons who have permanently migrated and are no longer ordinarily resident; individuals not found at the recorded address even after repeated visits; suspected non-citizens; and cases of multiple registrations—within the constituency, elsewhere in the State, or even in other States—undermining the core democratic principle of one-person-one-vote. Treating draft-level flagging as synonymous with “disenfranchisement” collapses the essential distinction between a contestable working document and a final exclusion.

And where the flag is wrong—as it will be, inevitably, in an exercise of this scale—the legal remedy is not exotic or inaccessible. The system provides simple claims and objections, followed by a straightforward appellate route. The ECI should be judged on how well these remedies are publicised, assisted, and decided, not condemned as a “farce” merely because the draft surfaces large numbers for verification.

Where parties must step up: less theatre, more field work

If that work is absent, two explanations are plausible: either the deletions are substantially justified, or party organisations failed to perform a basic democratic function while preferring rhetorical escalation. It is easier to denounce “mass disenfranchisement” than to do the decentralised, unglamorous labour the law contemplates.

Course corrections aren’t chaos

If not SIR, then what?

- Freeze existing entries and treat a polluted roll as sacrosanct?

- Abandon technology-assisted de-duplication and accept persistent multiple enrolments?

- Stop reconciling death and migration indicators because errors may occur?

None of these positions is defensible in policy terms. A credible reform agenda would look very different: better integration of civil registration of births and deaths data; clearer notice and reason-giving; standardised address protocols; trained and monitored field staff; time-bound disposal of claims; independent audit sampling; and simple online tracking for citizens. That is the terrain where criticism should land. The Hindu instead chose to delegitimise the exercise, offering no workable replacement.

Conclusion: scrutinise hard—without delegitimising or scandalising the mandate

On January 1, 2026, The Hindu had an opportunity to elevate the debate: insist on safeguards, demand better administration, and propose workable improvements—without equating administrative imperfection with constitutional collapse. It chose instead to delegitimise—indeed, to scandalise—the mandate and the underlying SIR process, while offering no credible alternative to clean rolls in a country of this scale.