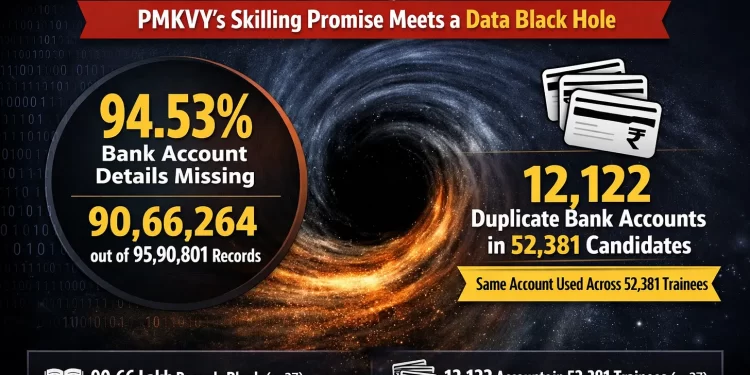

CAG’s Audit Report shows ‘bankAccountdetails’ blank in 90,66,264 of 95,90,801 records under PMKVY 2.0/3.0—and even among the rest, 12,122 accounts repeat across 52,381 candidates (p. 27, Table 2.2).

If Parliament Saw the Press Note, the Public Must Read the Hard Numbers

On 18 December 2025, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG)’s performance audit of the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY)—literally, the Prime Minister’s Skill Development Scheme—was presented in Parliament. A lazy way to write an op-ed would be to recycle the official CAG press release that followed. The more complex—and more responsible—way is to review the 108–page report laid before Parliament, sift its contents, and then ask what it implies for the scheme’s stated objective of skilling India’s youth.

That deeper reading produces a blunt conclusion: the CAG audit report is ruthless in what it puts on record, while the press release is diluted and mild in tone and tenor, selecting a few safe figures and leaving out the larger, uglier story of leakages and control failure. Let us address what matters most: hard statistics and where the maximum leakages have occurred.

The First Leak Was Not Money—It Was Data

Before money leaks, the system’s basic plumbing must fail. And here, the plumbing failure is not subtle.

Data analysis for PMKVY 2.0 and 3.0 shows that the'bankAccountdetails’ field was “zeros/Null/N.A./blank” in 90,66,264 out of 95,90,801 cases—94.53% (printed p. 27, Table 2.2 summary). In the remaining cases, 12,122 unique bank accounts were repeated across 52,381 participants (printed p. 27, Table 2.2 summary).

This is not a minor clerical defect. If the basic bank-account field is unusable for the overwhelming majority of records, then any claims of clean beneficiary transfers, clean reconciliations, or clean audit trails should make administrators uncomfortable. When foundational data is weak at this scale, the programme becomes vulnerable not merely to “errors”, but to organised manipulation.

The Youth Didn’t Just Miss Jobs; Many Missed the Promised Cash Support

During PMKVY 1.0, ₹40 crore of DBT remained unpaid due to incorrect/incomplete bank and Aadhaar details (printed p. 69). In PMKVY 2.0 and 3.0, DBT payments were still outstanding for about 34 lakh candidates (printed p. 69, with internal cross-reference to para 2.4.2.2). During a survey of trainees in ongoing batches, about 20% were not even aware of cash benefits (printed p. 69).

These are not “accounting losses” in the narrow sense; they are something worse: a direct defeat of citizen-facing delivery. If youth are certified and recorded in the system but benefits remain unpaid in lakhs of cases, the scheme begins to resemble a dashboard exercise rather than a reliable public service.

RPL-BICE: When Certification Becomes a Factory Line

Recognition of Prior Learning—Best-in-Class Employer (RPL-BICE) should have been a high-value instrument: certify real skills, formalise informal experience, strengthen employability. But the numbers show how large the risk became when safeguards were weak.

Under RPL-BICE, certification of 12.64 lakh candidates involved candidate payouts and assessment charges totalling ₹167.56 crore (printed p. 49, para 3.8, Table 3.7). That is a major stream of public spending riding on the integrity of assessment, evidence, and monitoring.

Now look at the audit’s own quantified risk signal: four BICEs together certified 1.24 lakh candidates, involving an assessment fee of at least ₹9.96 crore, even as the audit records suspected/edited evidence and criticises the Ministry’s tendency to treat DBT payout as “evidence” of genuine certification (printed p. 56, within para 3.8 discussion immediately preceding para 3.8.2).

Even more telling is the official defence offered when confronted with irregularities: “duplicate photos” were investigated and attributed to “human error at the time of upload”, with the reassurance that each certified candidate was paid only once through DBT (printed p. 56, para 3.8 discussion). But this logic collapses under basic scrutiny. Payment is proof of payment—not proof of valid assessment, not proof of genuine training/skill verification, and certainly not proof that documentary evidence was reliable.

When “certification at scale” is combined with “suspected evidence” and “human error” explanations, the system is no longer merely inefficient. It appears to be systemic fraud enabled by design weaknesses.

States: The Last Mile Where Funds Parked, and Youth Waited

The audit’s most damning federal reality check is that the state-level channel—supposed to be closer to the ground—often failed to spend, monitor, and deliver.

Out of ₹1,380.87 crore disbursed to States for PMKVY 2.0 and 3.0 during 2016–24, ₹277.40 crore (20.09%) remained unutilised as of March 2024 (printed p. 68, para 4.2.3). Worse, even in the pre-COVID period (2016–19), utilisation was only ₹149.85 crore against releases of ₹757.82 crore (printed p. 68, para 4.2.3).

This is not merely “delay”; it is administrative failure with consequences. Unutilised skilling funds are not like unspent stationery budgets. They represent youths who were supposed to be trained, assessed, supported—and were not.

And where funds were spent, basic rules were not always honoured. In Rajasthan, assessment and certification fee of ₹1.26 crore was paid directly to Training Partners instead of assessment agencies/assessors—explicitly violating the guideline principle of paying stakeholders directly to their bank accounts (printed p. 71, para 4.2.5).

This is precisely where a sharper political message is warranted: not against the Prime Minister’s vision or the scheme’s intent, but against state governments that failed in execution and compliance, and against a central oversight framework that allowed such weakness to persist.

The Centre’s Oversight: Big Sums, Weak Estimation, and Loose Control

At the centre of PMKVY’s financial architecture sits NSDC and the Ministry’s control environment. Here too, the record shows avoidable failure.

The audit’s fund-estimation and timing story is revealing: Table 4.1 records that PMKVY 1.0 includes ₹222.63 crore transferred by NSDC from unspent balance of the earlier STAR scheme (printed p. 63, Table 4.1). The narrative notes that the Ministry estimated only ₹65 crore was available with NSDC from STAR, while average balances of over ₹200 crore existed in 2014–16, and the ₹222.63 crore was transferred only in April 2018—after the first phase ended and the next phase had already launched (printed p. 63, para 4.1 discussion following Table 4.1).

That is not merely a bookkeeping quibble. Poor estimation and delayed fund alignment distort releases, distort accountability, and make it easier for money to remain “parked” rather than deployed for youth outcomes.

“Recovered” Money Is Not the Same as a Repaired System

A press note can claim comfort when money is “recovered”. The audit text shows why that comfort is premature.

NSDC earned additional interest of ₹12.16 crore (April–August 2019) on unspent PMKVY 1.0 funds that was not transferred and was retained, later recovered/deposited after audit observation (printed p. 72, para 4.3.1). NSDC also apportioned ₹46.36 crore as administrative expenses against admissible ₹22.23 crore, resulting in excess by ₹24.13 crore (printed p. 72, para 4.3.1). Crucially, the audit states that interest earned on the ₹12.16 crore from September 2019 onwards needs to be accounted and refunded, along with the excess administrative claim (printed p. 73, para 4.3.1).

So the real issue is not whether one amount was clawed back. The real issue is whether the system was ever designed to prevent such retention, mis-accounting, and excess charging in the first place.

District-Level Accountability Was Starved of Funds

Perhaps the most telling failure of oversight is what happened to district-level committees—the very layer that could have tightened monitoring.

During 2021–22, the Ministry released ₹644.27 crore to NSDC with instructions to release the relevant share to District Skill Committees—₹32.21 crore (5%)—yet those funds were not transferred by NSDC (printed p. 73, para 4.3.2). The explanation that “no claim was received” may be administratively convenient, but it is not an excuse. If districts are not drawing funds, that itself should trigger intervention, support, enforcement—and consequences.

A skilling programme cannot be run purely from Delhi dashboards. When the district layer is weakened, fraud risk rises and outcomes fall.

This Is Not a Case for Blaming the Scheme—It Is a Case for Saving It

None of this is an argument to target the Prime Minister’s vision or the concept of PMKVY. The stated national goal—industry-relevant skills, certification, employability—is essential. The problem is the implementation ecosystem: weak data safeguards, poor fund discipline, compromised evidence in certification streams, and uneven state performance.

When bank-account data is unusable at scale (printed p. 27), when benefits remain unpaid in crores and lakhs of cases (printed p. 69), when a certification stream runs into ₹167.56 crore with unreliable evidence concerns (printed p. 49; and quantified risk signals on printed p. 56), and when States leave one-fifth of released funds unutilised (printed p. 68), the honest label is not “teething issues”. It is systemic failure, and in parts, systemic fraud made possible by weak controls.

A Reform Signal the Government Should Not Ignore

The proper response is not denial, nor a cosmetically “mild” summary. It is reform.

The Ministry and the Government should treat these recorded facts as a hard signal to rebuild the system: strict data validation before any DBT linkage; unique-account and identity controls as non-negotiable; evidence-retention rules that make fabrication harder; and state-level accountability that ties releases to performance and compliance. Just as importantly, the system must stop equating payment with proof—a confusion that the audit narrative itself warns against in the RPL-BICE context (printed p. 56).

Skilling is India’s demographic promise. But a skilling scheme without safeguards does not merely waste funds—it risks manufacturing false confidence, while real youth outcomes remain uncertain. The country deserves better, and the youth deserve the programme that was promised.